Published on Dec 14, 1999

Why is “classic” Genesis so seldom played on “classic rock”

radio? There exist numerous theories on that subject, but one of

the more commonly-heard ones is that they are keyboard-heavy and

guitar-light compared to the Zeppelins and Stoneses of the world.

And the common misperception (at least when it comes to Genesis) is

that keyboards are wimpy instruments that should be either in the

background or completely removed if a song is truly to “rock”.

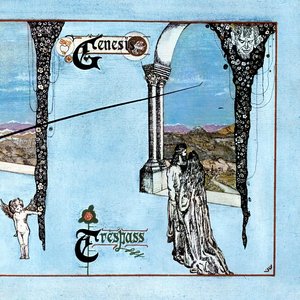

The five records Genesis recorded from 1970 to 1974 are reason

enough to renounce that belief, but if one needs to be eased from

guitars into keyboards in baby steps, one should start from the

beginning with

Trespass.

Trespass was not actually their first album — that

distinction belongs to 1969’s oft-maligned

From Genesis To Revelation, a pastoral, string-heavy pop

record that isn’t as bad as many think it is, but is a far cry from

what this band would do shortly thereafter. Thrown into a cottage

in the woods and living together at the suggestion of their

producer, the lads from Charterhouse Boarding School, all barely 20

years old, survived close quarters, and out came six intense pieces

that sounded like nothing recorded since.

The stark, spare first verse to “Looking For Someone” opens the

album, and in extreme contrast to much of the frothiness of the

previous record, Peter Gabriel is “Trying to find a memory in a

darkroom” and “Lost in a subway.” The song launches ambitiously

into several tempo and mood changes — Anthony Phillips plays some

immaculate guitar that has more of a classical feel than most of

his rock contemporaries, partly for the purpose of making sure that

Anthony Banks’s organ playing is not relegated to the

background.

In the coda, Gabriel gets in on the act himself with some

amazing echoey flute that blends in perfectly. Short-lived drummer

John Mayhew has a more monotonic, less professional style than Phil

Collins (who would become the Genesis drummer a year later and the

singer six years later), but he certainly holds his own, especially

here, where he sounds equally controlled and manic. “White

Mountain” follows and is less accessible, but just as unique, a

mythical prog-rock tale with a swelling, King Crimson-esque

mellotron.

Fans of Gabriel’s more recent solo work will enjoy the

Phillips-penned “Visions Of Angels.” It’s actually the closest they

come to sounding like they did on the first album, but is still

leagues ahead. The organs and mellotrons are toned down to a piano

for the most part here, and Gabriel does some of his most soulful

and philisophic singing ever — “Some believe that when they die

they really live / I believe there never is an end.” It’ll be tough

to accept “Sledgehammer” as any sort of artistic statement after

listening to this.

Side two arrives, and with it “Stagnation,” excerpts of which

Genesis was still playing live on the

We Can’t Dance tour. The folksy first section includes an

as-yet-unduplicated mixing of classical guitar and keyboard into a

single sound that is so beautiful and simply indescribable. And

like “Looking For Someone,” the alternating sections of loud and

quiet, start and stop, work so well together; never do you wonder

“Is this still the same song?” Rather, the drawn-out final section

can’t go on long enough — the dramatic drumroll and off-key chaos

that finally brings this eight minute opus to an end has the feel

of the sad end of a performance that just makes you want more.

“Dusk,” at four minutes the shortest track on the album,

initially serves as little more than a head-clearing exercise for

what’s to come next, but it’s actually a very good song. Less

ambitious than the rest of the album, but still a distinguished,

spiritual acoustic number about a new beginning.

And then, in sharp contrast, comes “The Knife,” which closes out

the album with what is still the biggest bang in Genesis history.

It’s a monstrously heavy number, containing elements of British

Invasion hard rock a la Deep Purple or Uriah Heep. Even the lyrics

are heavier, speaking words of uprisings and revolutions on an

album otherwise chock full of introspection. And of course, there’s

yet another lengthy coda here, full of tempo changes and

intelligently-sequenced shifts from minor to major variations of

the same musical themes. The chorus- – “Some of you are going to

die / martyrs of course to the freedom that I shall provide”

returns at the end over a spine-tingling major seventh flourish,

and even the ensuing silence is deafening.

“The Knife” was clearly a live favorite for many years; it once

inspired Gabriel to fling himself into the crowd, resulting in a

broken leg, but in spite of that, the band continued to perform it,

often as an encore, well into the Collins era. In today’s world of

noisy rock, it’s surprising they haven’t resurrected it. But “The

Knife,” and

Trespass in general, is also the first indication of what

separated Genesis from other “art rock” of that era; the ability to

create a lengthy, multi-layered piece of music without losing sight

of the song at hand. Rather than filling up space with lengthy,

unmemorable solos, the 7 to 10 minute Genesis epics are filled with

notes that mean something, meticulous instrumental sections that

flow just as naturally as concise radio friendly songs.

On more complex later albums like

Foxtrot and

Selling England By The Pound, the Genesis without Phillips

but with Collins and Steve Hackett would eclipse even these highs,

but

Trespass has a spontaneous, innocent quality that they never

quite reached again. It’s the sound of a rapidly maturing rock

collective (early Genesis never separated songwriting credits in

their liner notes; “all songs written by Genesis” was the standard

copy) in its most fruitful period and hungry to be heard. If you’re

still a relative newcomer to early Genesis, it’s probably best to

start slightly later chronologically, but this is a logical next

step.