Published on May 29, 1999

The Beatles retired from live performance in 1966, after a

three-year period of whirlwind global tours. For the remainder of

their career, they would focus their creativity in the studio, and

produce a series of LPs so wide in scope, songwriting skill, and

musical craft that the five full records produced –

Sgt. Pepper’s,

Magical Mystery Tour, the “White Album”,

Abbey Road and

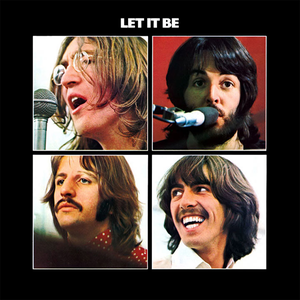

Let It Be – are all among the pantheon of truly classic pop

albums.

(Diehard Beatles fans can skip the next couple paragraphs, which

will briefly chronicle the tumultuous days at Twickenham that

produced this album and began the breaking-up process of the

group)

In 1969, the Beatles reconvened with two goals in mind – perform

live and document the preparations for said concerts in film. Paul

McCartney, the originator and organizer of the project, put all his

energies into putting this plan into action. Unfortunately, the

other members of the group began to have second thoughts. McCartney

and John Lennon’s friendship was being tested already by Lennon’s

obsession with “avant-garde” “artist” Yoko Ono, and Lennon’s

drug-addled ambivalence to the project as a whole didn’t improve

matters. George Harrison entered the sessions after an eye-opening

period of jamming with Bob Dylan and the Band, determined to have

more songwriting input on the new album. The rejection of material

like “All Things Must Pass” and “For You Blue” early in the

sessions frustrated him to the point that Harrison actually left

the group for a period during January.

Finally, it became clear to the group that the live concert

appearance was simply not feasible. The group remained interested

in the idea of a “live in the studio” approach, free of the George

Martin studio pyrotechnics that so colored

Sgt. Pepper’s and the “White Album”. A decision was finally

made to haul the group’s equipment to the roof of the Apple Records

building, plug in the amps, and fire away. The Beatles (joined by

keyboardist Billy Preston) played a brief set before being shut

down by the police. They returned to the studio, but internal

turmoil and financial issues caused an abandonment of the

Get Back project. The rehearsal tapes were handed to

engineer Glyn Johns to put into a releaseable form. The results

were rather dire. Finally, after the Abbey Road sessions in

mid-1969, producer Phil Spector surveyed the wreckage and produced

the controversial mix of

Let It Be that was released in May 1970 – the last Beatles

LP.

Let It Be is probably the most underappreciated Beatles

album (if such a thing is possible) – eclipsed by the immensity of

the “White Album” and the inspired genius of

Abbey Road. It is an eclectic ten-song collection (the other

two tracks are short excerpts from the rooftop concert tapes) that

runs the gamut from hard-nosed rock to pretty ballads to playful

romps. Some of it is live, some very studio-ized. Although perhaps

not up to the consistent excellence of

Abbey Road and the “White Album,”

Let It Be is a tight, energetic album that captures the

Beatles’ power even during the depths of their intraband

conflicts.

Opening with a brief (and relatively hilarious in a British way)

spoken word segment, “Two Of Us” kicks off the album – a pretty

McCartney track featuring the standard vocal harmonies, plodding

rhythm section, and thoughtful lyrics. The theme is “going home”,

perhaps a reference to the group’s return to its roots, or perhaps

to their impending breakup. “I Dig A Pony” is next, a Lennon bluesy

number with mainly nonsensical lyrics with a very catchy chorus.

Preston’s organ beefs up the sound, and the electric guitar solo

(presumably by Harrison) is quite effective. Two very good tracks

to open up the album – both classic Beatles cuts that have been

sadly underrated.

Next comes Lennon’s sublime ballad “Across The Universe,”

another largely forgotten track that to my mind is the outstanding

piece on the album. Much like his masterpiece “Because” on

Abbey Road, “Across The Universe” is backed by incredible

harmonies and a simple, understated acoustic theme. A wierdly

disembodied choir swells during the choruses and adds to the

musical tension. A piece of sublime beauty that is definitely one

of my ten favorite Beatles cuts.

The first of Harrison’s two contributions to

Let It Be, the strangely Russian-flavored “I Me Mine,”

follows – a rather nasty attack on what Harrison perceived as the

egotism of the dominant Lennon-McCartney axis of the band. While

far from his

Abbey Road masterpieces, “I Me Mine” showcases Harrison’s

ability to create a catchy melody around an almost menacing

electric guitar riff. Preston’s organ vamps during the bridge are

very notable. Next comes “Dig It”, another funny section of the

live show, a 45-second excerpt from a longer jam that basically

consists of Lennon yelling out random things over a funky, crunchy

organ lick.

“Let It Be” is next, and probably needs no introduction. One of

the most famous songs of all time, it is McCartney at his best as a

songwriter and lyricist. Harrison’s immense guitar solo and the

pounding orchestral crescendo pull this song to its end. Side one

ends with “Maggie Mae”, another 40-second excerpt, this one of a

song about a Liverpool prostitute.

Side two begins with “I’ve Got A Feeling”, one of the last real

Lennon-McCartney joint compositions. Another upbeat rocker recorded

live, it is pleasant but falls short of the mark set on the first

side. “The One After 909,” ironically one of the first songs ever

written by the two, in the late ’50s, is resuscitated here, and

basically sounds like it logically should – an early bluesy Beatles

song augmented by Preston on electric piano.

George Martin, who did much of the pre-production on

Let It Be, often described the record as having been

“produced by George Martin, over-produced by Phil Spector.”

McCartney voiced similar complaints after the album’s release. Most

of this criticism has been aimed at this version of “The Long And

Winding Road.” Another pretty understated McCartney vocal ballad

was beefed up by massive orchestral and choral tracks – although,

allegedly, this was necessary due to the utterly half-assed

bassline Lennon had offered for the tune. Frankly, I think it is

overdone a bit, although I wouldn’t honor the more venomous attacks

(“Muzak”) that have been leveled at it in the past. Then again, I’m

not real fond of the song anyway…

“For You Blue” is the other Harrison song, and isn’t really all

that noteworthy, although Lennon’s slide guitar is kind of neat.

The album closes with the one-time title track, “Get Back”. Those

familiar with the single version of this will be moderately

surprised by the album version – a live take from the rooftop

session – which is substantially shorter and rocks harder than the

earlier version. An outstanding song, it begs the question of what

the finished product of a really concerted

Get Back project would have been.

This is another Beatles classic record. While probably the

hardest of the post-touring LPs to “get into”,

Let It Be is enjoyable if a bit odd in its jumps from live

to studio, jams to carefully arranged tunes, and sparse to lush

production. Recommended, but only after cutting your teeth on

Abbey Road, the “White Album,” and some sort of collection

of the other mid-60s material (“Strawberry Fields Forever”, “Penny

Lane”, “Hey Jude”, “Revolution” etc.)

Let It Be may lack the ethereal aura of genius and magic

that surrounds much of

Abbey Road, but it is an enjoyable album, well worth having

or hauling out for a play now and again. Oh, and yes, John, you did

pass the audition with this one.